What’s in a Street Name? The Paved-Over Past of L.A.

The Tribal President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians explains the roots of the ground we walk on

Published May 3, 2022

The megalopolis of L.A. County is a concrete collage of more than 50,000 crisscrossing streets, the highways like steel lattices stretching out for miles. With satellite-enabled global positioning system maps at our fingertips, we zoom along these manufactured arteries that spill into neighborhoods from beaches to canyons to valleys.

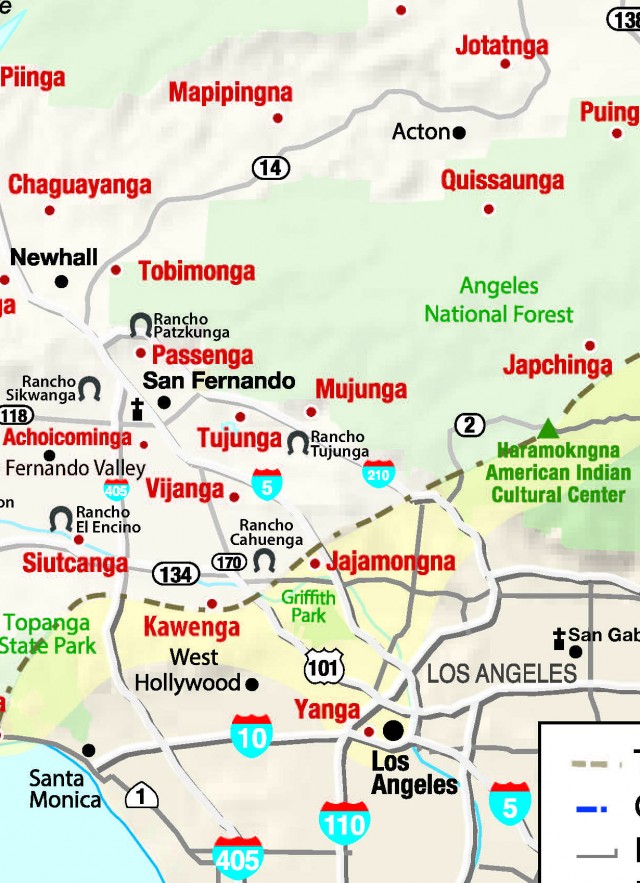

But while finding your way through the Southland, most of us may be unaware of the cultural histories behind the street names that guide our journey. Some of the signposts we may have thought were Spanish or Mexican words actually commemorate the sacred spaces of Indigenous peoples who have lived on this land for thousands of years. Native American Indian names are found on major boulevards—Topanga, Cahuenga, Malibu, Tujunga—all names of Chumash, Tataviam, and/or Tongva tribal villages. The traffic lights at these intersections, and others around L.A., blink around the clock, beckoning pedestrians and drivers to be alert to their surroundings. They could also, potentially, illuminate our past.

Rudy Ortega, Jr., the Tribal President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians, wants to bring more awareness to the undiscovered map of L.A., this fraught and layered geography. The Fernandeño Tataviam is the historic tribe of northern Los Angeles County whose ancestral villages are from the San Fernando, Santa Clarita, east Simi, and Antelope Valleys.

Fernandeño refers to the people who were removed from their homes and forced to register at Mission San Fernando, established on September 8, 1797 at the village of Achoicominga. Tataviam translates to "people facing the sun” named for those who lived on the south-facing sides of the mountains.

The history of California's native people is one of enslavement, relocation, broken treaties and genocide over hundreds of years by Spanish, Mexican, and Anglo settlers. One historic injustice leveled on the Fernandeño Tataviam community dates back to when the San Fernando village land was sold without the consent of tribal captains. In the late 19th century, Tribal Captain Rojerio Rocha fought to preserve the lands, but was dispossessed by ex-California State Senator Charles Maclay, who evicted Rocha through the courts and brute force. Now Ortega, who comes from a line of tribal leaders, is requesting that the City of San Fernando adopts a resolution to rename Maclay Avenue to Tataviam Tribe Avenue. President Ortega talks with us about this and more.

Which street names across L.A. belong to native Indian tribes?

RO: Tujunga, the road comes from village name; it was [later] a Mexican land grant given to an ancestor of tribe. Cahuenga is similar, many people think it’s a Mexican or Spanish word, but a lot of California has native words as well. The titles were lost but the street names remain. Topanga, is another. All those roads were just trails, but then settlers came in and altered things.

Topanga Canyon Boulevard, curving from the sun-baked valley to the Pacific Ocean, bears the name of the Native American village of Topanga which means the "where the mountain meets the sea." Today, the original people of Topanga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam, Gabrielino Tongva, or Ventureño Chumash Tribes.

Cahuenga Boulevard is named after the Native American village of Kavwénga which means the “place of the hills.” Today, the original people of Kavwénga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

Upper Tujunga Boulevard is named after the Native American village of Tujunga which means the “place of the old woman.” Today, the original people Tujunga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam or Gabrielino Tongva Tribes.

1 of 1

Topanga Canyon Boulevard, curving from the sun-baked valley to the Pacific Ocean, bears the name of the Native American village of Topanga which means the "where the mountain meets the sea." Today, the original people of Topanga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam, Gabrielino Tongva, or Ventureño Chumash Tribes.

Cahuenga Boulevard is named after the Native American village of Kavwénga which means the “place of the hills.” Today, the original people of Kavwénga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians.

Upper Tujunga Boulevard is named after the Native American village of Tujunga which means the “place of the old woman.” Today, the original people Tujunga are affiliated with the Fernandeño Tataviam or Gabrielino Tongva Tribes.

What progress has been made to honor these places?

RO: When we passed Indigenous Peoples Day, the City put in motion an effort to find Native places that need to be re-indigenized by adding history markers on [Spanish] Mission sites. That’s making sure people are aware of the history that the people went through and, the suffering, the atrocities that occurred to them, and that they managed to survive. In the 1840s, there were 41 families, but a total of five families that we have knowledge of have survived; so that is a huge impact. What survived more so than our people were our names. Like Cahuenga, Tujunga, Topanga, but there are no references to their tribal connection, or the languages of the first people before European contact.

Photo courtesy of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

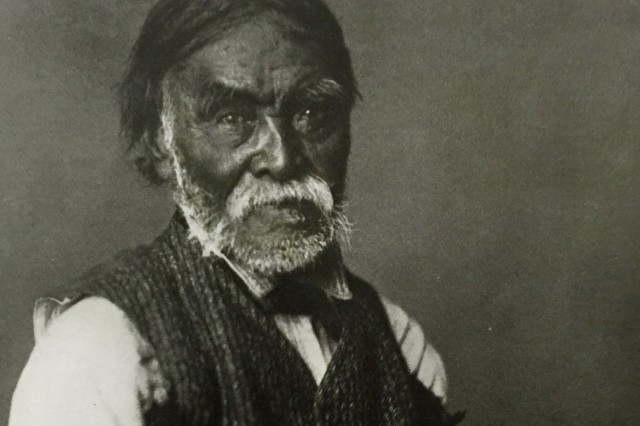

Rudy Ortega Sr., served as the Tribal President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians for over fifty years.

Photo courtesy of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

In the late 19th century, Tribal Captain Rogerio Rocha fought to preserve the lands, but was dispossessed by ex-California State Senator Charles Maclay, who evicted Rocha through the courts and brute force.

1 of 1

Rudy Ortega Sr., served as the Tribal President of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians for over fifty years.

Photo courtesy of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

In the late 19th century, Tribal Captain Rogerio Rocha fought to preserve the lands, but was dispossessed by ex-California State Senator Charles Maclay, who evicted Rocha through the courts and brute force.

Photo courtesy of the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians

What features of the land were L.A.’s earliest city planners attracted to?

RO: When you look at the city developing, they're usually looking for natural springs or places with easy access, and those are typically where the villages were initially. So, all of the downtown Los Angeles was the Tongva village of Yaanga. And then you have the village where University High School is: the Kuruvungna Springs. The Gabrielino/Tongva are managing the property there, which is fantastic because then they're able to maintain that and have access to the Springs and the grounds. So those are places that are deep into Los Angeles, now this huge metropolitan area.

How do we acknowledge this history?

RO: These places where it needs to be re-indigenized, right? So we have like, for example, San Fernando Mission Road Boulevard, right in front of the San Fernando Mission, the cross street is Columbus Avenue. The street goes all the way across the Valley, North and South, and so that's a huge undertaking to replace that name. There is a motion to designate these areas with history markers that say, when you go to the Mission, there on the street post or somewhere it says ‘here's a village.’”

What is the origin of the term “land acknowledgement?”

RO: Land acknowledgment is an ancient protocol. When I was doing a lot of spiritual and cultural training in my late teens and early twenties, I had to do it, and acknowledge the land that I wanted to go travel to. There's a whole ceremonial process. You wait until the elder—the spiritual or cultural leader—permits you to engage in the program, in the song and dance. We just took it and made it contemporary. And now we're saying folks who are not Indigenous are part of this huge political and social network of America and should acknowledge the first peoples of these lands in order to bring the history out; That's the key. Today we say the word “developed,” but it wasn't developed well; it was always lacking, missing, and incomplete, and the reason is because they robbed and stole from someone else, the Indigenous community, to create something different on top of it. Therefore, it has a weak foundation. It's never going to be strong enough.

The only way to have very unified and diverse communities is if the foundation is strong. Los Angeles with over 10 to 12 million people in the city, and only a bucket, a droplet of those people know about the tribes and know about the street names being Indigenous. And so that's a very small percentage. That's why we’ve got to bring more awareness out there.