Our Bird Curator's New Perch

Meet Dr. Allison Shultz, the museum’s new Assistant Curator of Ornithology.

Check out this interview with Allison on Science Friday!

Read more about Allison's work on avian vision and color.

Originally published in 2018

“My bird senses are ringing,” says Dr. Allison Shultz, the museum’s new Assistant Curator of Ornithology, as she walked through the Nature Gardens recently. Amid the laughter of children and cars whooshing by, she hears a lesser goldfinch singing up in the trees and then a black phoebe calling. “Hear that? It sort of sounds like a dog’s squeaky toy.” As we round the corner into the Pollinator Garden, she detects an Allen’s hummingbird’s distinctive tweet and then spots him beating the autumn air with his iridescent wings.

Shultz, who grew up in Dana Point along the Orange County coast, can trace the evolution of her avian infatuation to a course she took as an undergrad at U.C. Berkeley on the natural history of vertebrates. She got “hooked on birds” and decided to research campus bird life by looking at historical records and seeing how that college-bound community changed over time.

Since then, Shultz’s academic flight path has taken two routes — the study of bird color and also their genetics. For her master’s degree at San Diego State University, she researched the brilliantly plumed tanagers, whose color sometimes allows them to blend into the background and to hide from predators. Feathers, which exist in a rainbow of hues, also signal a bird’s species and overall health. The brighter the bird, the healthier it is because it takes more energy to produce that attractive shade (red-feathered foul are more likely to be mate-magnets). The ornithologist is a portrait artist, too. The walls of her office are decorated with paintings of tanagers in a tree as well as the vivid green-feathered turaco, which evolved to make its own pigment.

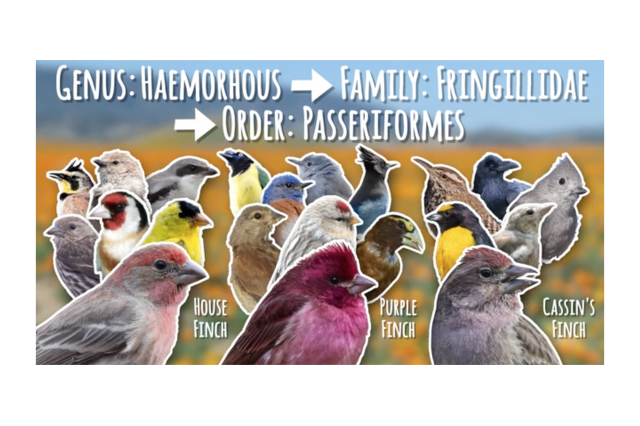

LOTS OF FLOCKS

Her second area of research, genetics, looks at these creatures from the inside. At Harvard University, where she earned a PhD, Shultz studied how house finches, after being introduced to the East Coast in the 1940s, evolved in their new habitat. Now at NHM, she’s excited to train her binoculars on the skies of L.A. — the “birdiest county in the U.S.,” from the standpoint of species diversity. “L.A. is a mix of people but also a mix of birds,” she says. She wants to know more about the interactions between native and introduced species occupying our airspace, and that’s something humans can help her with. Community science participants who capture and share their observations can offer data on how bird communities here are changing. For instance, are certain species of parrots or songbirds taking up residence in new or different habitats? And how are our nonnative avian neighbors thriving in our museum’s outdoor spaces? Visitors can see one successful example — house sparrows that hail from Europe regularly make a rumpus in the Edible Garden.

REST YOUR FEATHERS

The Nature Gardens, with 600 species of plants, is designed to be a green oasis.

In urban areas like this, there are larger swaths where there's just not a lot of plant life, especially the native plants that these birds really rely on to get the nutrition they need, and for their nesting materials.

Dr. Allison Shultz

Having these gardens available gives these birds — even if they’re just passing through — a place to rest and refuel, she says. A Southern California native, Shultz is thrilled to have landed at the museum, where the flocks are familiar. “It’s amazing here, like coming home to old friends.”

BIRDS ALL AROUND

Birds are everywhere at NHM. In NHM's Dinosaur Hall, see how birds (modern dinosaurs!) evolved and explore the stories of avian interlopers, such as parrots, in the Nature Lab. Outside, discover hummingbirds and finches at the feeders in the Nature Gardens and listen for the tweets on garden tours with our educators who may point out a flyer or two stopping by.