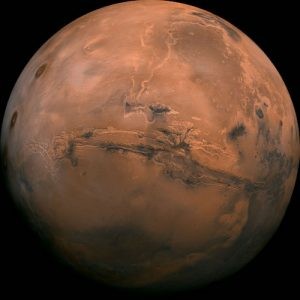

Minerals on Mars

Scientists have long wondered if Mars could support life. But what exactly should we look for?

“Biosignature” is a really cool word you hear a lot when people talk about finding life on other planets or moons. Because we’re looking for tiny microbes (that may have been dead for many millions or billions of years), scientists aren’t looking for life per se, but instead, signs of life — evidence of current or past living things, which is what a biosignature is.

Scientists have long wondered if Mars could support life, now or in the past. As far as the planets in our solar system go, it’s the most likely place, because water once flowed on its surface (and signs of super briny water flows remain today). But what exactly should we look for on Mars? It sounds like trying to find a microscopic needle in a very big haystack. NHM Mineral Science Curator Aaron Celestian is interested in the special role minerals play in this question. “How do you go to a different planet, zap a rock, and figure out that there are biosignatures in it?” he asks.

To help answer this question, Celestian is collaborating with Scott Perl, a research scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech who specializes in geobiology and astrobiology — the study of life on Earth and elsewhere in the universe. They’re considering what biosignatures we could potentially look for on the Martian surface. A likely biomarker (a specific chemical to test for) is a group of molecules called carotenoids, the most famous of which is beta-carotene — the pigment that makes carrots orange.

“Microbes on Earth use carotenoids to protect themselves from harmful UV light, and there is a great need for that on Mars because its atmosphere is so thin it doesn’t filter out the UV light coming from the sun,” said Celestian.

If microbes on Mars used (or use) similar pigments to protect themselves, they would be a very convenient biosignature for two reasons: 1) They don’t occur randomly on their own — they are only made by living things, and 2) They are easily identified among the minerals on the Martian surface with an instrument called a Raman spectrometer.

“Through our JPL, NHM, and USC Earth Sciences collaborations we’ve pioneered new methods to examine these chemical biomarkers,” said Perl.

The next NASA mission to Mars is called Mars 2020 — named after its destination and the year it will launch. It will send an SUV-sized rover to the Red Planet to learn more about our planetary neighbor, especially whether or not it has ever supported living things. And it just so happens to include a Raman spectrometer, the device that could potentially look for carotenoids in the Martian regolith (the scientific term for dirt on other planets and moons, since “soil” technically includes living things).

What are the odds of finding living things there? Celestian is an astrobiological optimist. “I am hopeful that there is a chance for living bacteria on Mars.”

Perl shares his optimism: “The minerals Aaron and I are investigating have the ability to protect microbial life and its biomarker evidence. If life were ever to have been present on Mars, I’m confident we can find it.”