How Littler Raptors Are Making It in the Big City

Picturing the perfect city raptor with community science data

Being a raptor is more of a vibe than a strict definition.

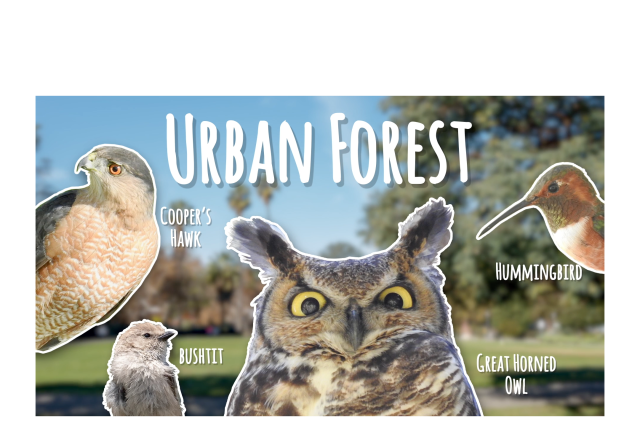

Okay, maybe more of a lifestyle than a vibe according to Allison Shultz, Associate Curator of Ornithology and scientist in the Urban Nature Research Center at NHM: “I would say my definition of a raptor is something that has a really sharp beak and really sharp claws and hunts things.” So, birds that aren’t closely evolutionarily related could still be raptors. Falcons? Raptors. Eagles? Raptors. Owls? Some of them are raptors. Hawks? You better believe they’re raptors.

Raptors are a broad grouping of birds that includes species like this great-horned owl (Bubo virginianus).

image by iNaturalist user radrat

What connects bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and great-horned owls besides their good looks? The raptor lifestyle of using sharp beaks and talons to hunt prey.

image by iNaturalist user chrismcv

1 of 1

Raptors are a broad grouping of birds that includes species like this great-horned owl (Bubo virginianus).

image by iNaturalist user radrat

What connects bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) and great-horned owls besides their good looks? The raptor lifestyle of using sharp beaks and talons to hunt prey.

image by iNaturalist user chrismcv

Raptors have a particularly interesting perch in the food web, a perch humans are constantly tearing down (and occasionally inadvertently reengineering) as cities continue to grow. To better keep these birds safe, scientists need to know which species struggle the most with city life, a question Shultz and her colleagues explored in a recent study published in the journal Ibis.

Found on every continent except Antarctica where they dine on everything from roadkill to pigeons in flight, the bird family Accipitridae (which includes hawks, eagles, and some vultures among other birds of prey) were the perfect candidates to find out what traits help a raptor succeed in city living.

Shultz and her colleagues looked at the bird family Accipitridae which includes hawks and other birds of prey like this golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) which struggles in urban environments.

image by iNaturalist user hannawacker

Hooded vultures (Necrosyrtes monachus) like this are also in the family. Carrion feeders face unique challenges like carcasses poisoned with lead ammunition.

image by iNaturalist user francescocecere

Peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) were not included in this study as falcons are only distantly related to hawks and eagles. They've evolved into raptors independently of hawks and eagles in the Accipitridae family. image by iNaturalist user stephenmatthews

1 of 1

Shultz and her colleagues looked at the bird family Accipitridae which includes hawks and other birds of prey like this golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos) which struggles in urban environments.

image by iNaturalist user hannawacker

Hooded vultures (Necrosyrtes monachus) like this are also in the family. Carrion feeders face unique challenges like carcasses poisoned with lead ammunition.

image by iNaturalist user francescocecere

Peregrine falcons (Falco peregrinus) were not included in this study as falcons are only distantly related to hawks and eagles. They've evolved into raptors independently of hawks and eagles in the Accipitridae family. image by iNaturalist user stephenmatthews

“Having sightings from all throughout the urban area, so not just in the park, but on the corner, in the middle of the city, that's where these types of observations are actually really important. Every observation that community scientists make is important.”

How do you bird-watch across five continents without leaving home?

To get a better picture of how these birds are coping, Shultz and company relied on observations submitted to eBird, an online bird observation database (like iNaturalist, but just for birds). Community scientists in 59 cities across the planet provided a rich data set to explore global raptor populations. The more frequently a bird was observed over time in the heart of cities versus the surrounding countryside, the better it was handling the urban environment. Satellite imagery and Apple Maps data helped bring the urban bird environment into focus and identify the core of big cities. “This study couldn't have been possible without community science and using either eBird or iNaturalist,” says Shultz.

Shultz and her colleagues looked at five traits they thought would best predict which birds would do well in an urban space: mass (how big is your bird), diet breadth (how many different things a bird eats), habitat breadth (can they live in different environments), whether or not they migrated, and nest substrate breadth (how many places they can build a nest). The study found success came down to body size and the ability to live and nest in different spaces.

Bird real estate markets: Habitat breadth and nest substrates

“Habitat breadth really is how many different types of habitats can these species live in and thrive in,” says Shultz, so it’s understandable that a species can survive in a city, where there might be a mix of hardscapes like overpasses or skyscrapers, individual trees and green spaces like parks or even medians. A habitat generalist isn’t as picky about their neighborhood. They can better deal with the fragmentation of space happening in cities. The same idea applies when thinking about nest substrates: “Birds that can nest on manmade structures or trees planted throughout urban spaces are the ones that are doing the best. The more different places you can nest, the better you do in a city.”

Birds like the red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) are able to take advantage of our urban environments, while other birds struggle. “Something like the white-tailed kite– species that need a lot of open space or very open habitats so they can really see long distances and find particular prey, they're species that are not doing well in urban areas.”

image by iNaturalist user radrat

Smaller birds in cities

Bigger isn’t better for birds in urban cores. The study found that mass was the other big trait that let a raptor reside close to the heart of the city. Species that fall into the lower end of the scale are right for urban living. So what’s the ideal city dweller? “Something that's pretty small to medium size, definitely not a big raptor, and something that's fairly generalist in its habitat, in its dietary preferences. So the Cooper's hawk is an excellent example of the archetypal city raptor.”

Lucky for Cooper’s hawks, cities are full of the pigeons and house sparrows they love to hunt. Another recent study showed that Cooper’s hawks have continued to thrive in L.A. while larger raptors like golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) vanished from the urbanizing areas, but the picture is more complicated than any single factor playing the decisive role in raptor success. While not a subject of this study, the very small American kestrel (Falco sparverius) has proven unable to survive in urban spaces.

Community science helps raptor and human communities.

Global studies like this can help us protect more vulnerable raptors as urbanization continues, informing decisions we make on the local level, and protecting the birds on your block. “That's where community science can really play a role in starting to think about that fine-scaled detail of where these birds are living and what's the neighborhood like that they're living in,” says Shultz. Crowd-sourced data can illuminate human injustice through the lens of biodiversity, helping researchers like Shultz and local communities explore new, pressing questions going forward. “We need to understand the specific aspects of what humans are doing to the environment and how biodiversity correlates with issues related to social justice, for example, the availability of green space.”

So where can you see raptors in the city? “I would say look up because a lot of times they'll be soaring, you know? So look in the sky,” says Shultz. Really any place high up is a good place to spot a raptor: light poles, tall trees, wherever they might have a good view of unsuspecting pigeons. “I see hawks perched all the time next to the freeway because it's a high perch with a big open area so they can see really far.” And as long as you’re not the one driving, be sure to take a picture.

“Having sightings from all throughout the urban area, so not just in the park, but on the corner, in the middle of the city, that's where these types of observations are actually really important,” says Shultz. While you keep an eye out for raptors, don’t overlook common birds. “Every observation that community scientists make is important.”