Beyond Gender: Indigenous Perspectives, Mapuche

A limited series on some of the world's third gender Indigenous people

Published September 15, 2020

Source for the above video: Youtube: Alberto Gonzalez Rodriguez

Connecting Our Past and Present

The Anthropology Department in partnership with the Community Engagement team are excited to share contemporary stories and NHM collections items spotlighting the Mapuche, Muxe, and Fa'afafine and Fa'afatama. Follow along for two additional stories linked below highlighting these vibrant and diverse third gender communities from all around the world.

The gender binary system that exists within many western societies is far from a universal concept.

In fact, numerous Indigenous communities around the world do not conflate gender and sex; rather, they recognize a third or more genders within their societies. Individuals that identify as a third gender many times have visible and socially recognizable positions within their societies and sometimes are thought to have unique or supernatural power that they can access because of their gender identity. However, as European influence and westernized ideologies began to spread and were, in many cases, forced upon Indigenous societies, third genders diminished, along with so many other Indigenous cultural traditions. Nevertheless, the cultural belief and acceptance of genders beyond a binary system still exist in traditional societies around the world. In many cases, these third gender individuals represent continuing cultural traditions and maintain aspects of cultural identity within their communities.

Within a Western and Christian ideological framework, individuals who identify as a third gender are often thought of as part of the LGBTQ community. This classification actually distorts the concept of a third gender and reflects a culture that historically recognizes only two genders based on sex assigned at birth - male or female – and anyone acting outside of the cultural norms for their sex may be classified as homosexual, gender queer, or transgender, among other classifications. In societies that recognize a third gender, the gender classification is not based on sexual identity, but rather on gender identity and spirituality. Individuals who identify with a cultural third gender are, in fact, acting within their gender/sex norm.

Mapuche, Chile

Some Indigenous societies have co-gendered individuals that take on the role of shaman or healer. These individuals can go between earthly and spiritual worlds and, in many cases, can flow between genders. Among the Mapuche people in Southern Chile and adjacent areas in Argentina, Machi are considered religious authorities capable of balancing the Mapuche cosmos. The Machi gender is determined by their identity and spirituality, not by sex assigned at birth. This fluidity of gender is what provides them the ability to interact with the spiritual realm.

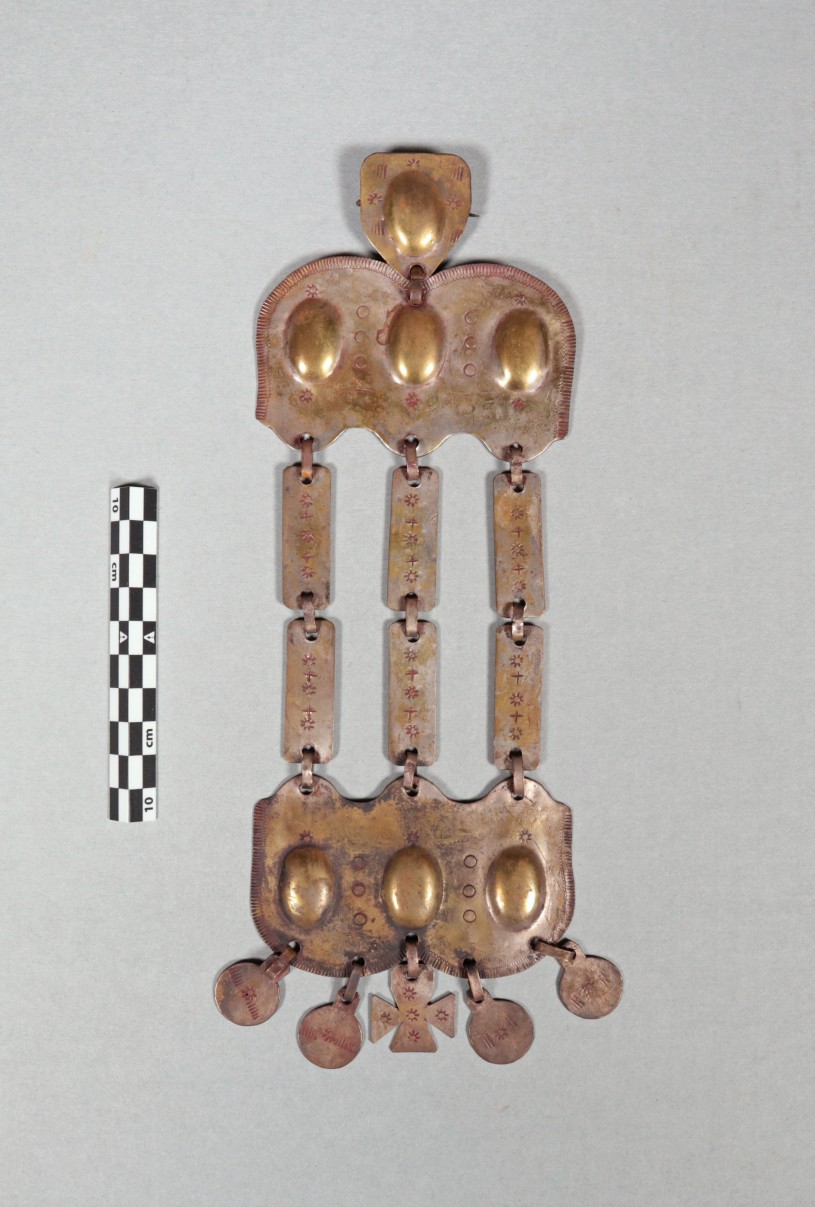

To the Mapuche, life is about balance; a dualist perspective blending opposing and complementary concepts within the realms of sky and earth, good and evil, and feminine and masculine behavior. The symmetry of this pendant pictured below, called a trapelacucha, symbolizes this duality.

The Chilean trapelacucha pictured is from 1938-1941. It is decorated with incised sunbursts and equilateral crosses. The equilateral cross is a recurring symbol also featured on traditional drums and in the center of the Mapuche flag (images below). According to Mapuche linguists María Catrileo and Gloria Quidel, the cross “indicates the spaces into which the world is divided - the four natural and spiritual positive and negative strengths that correspond to the land of the east, north, sea and south.” Machi wear the trapelacucha because they believe that silver protects them from evil spirits.

Mapuche culture is known for its silver ornaments made from the silver coins received from the Spanish after political negotiations or as payment for goods. The history between the two groups was a hostile one indeed, but trade persisted in times of decreased tensions.

The object's documentation notes that the design on the inside of the bowl of this spoon (which was actually used as a shawl pin) may be a cactus. If so, it could possibly be a chupasangre cactus, whose large tuberous roots and fruit have been collected and consumed for centuries by the Mapuche.

Mapuche still thrive today.

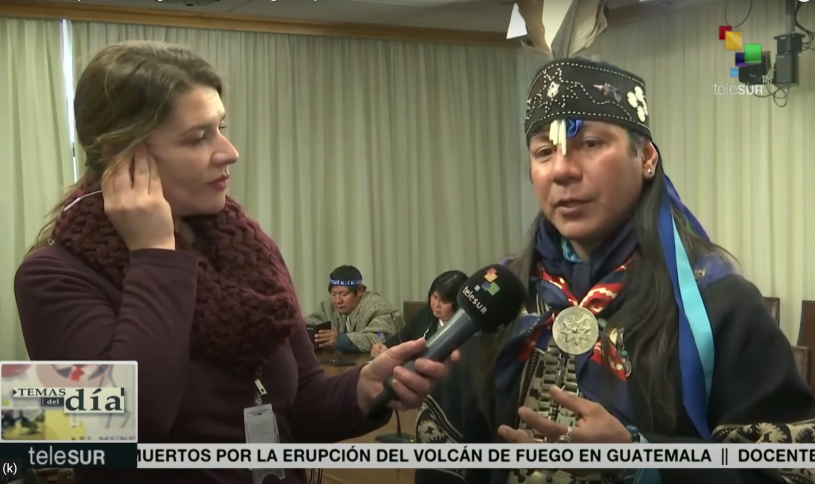

Today, the Mapuche people make up the largest Indigenous community in Chile and like the Indigenous communities discussed in this limited series, they tirelessly work toward keeping their language and cultural traditions alive. The trapelacucha continues to be worn by Machi leaders and a contemporary version of the pendant can be seen in the image below, worn by Machi Jorge Quilaqueo. Machi Jorge is seen here meeting with the Chilean government and media to discuss the release of political prisoner Machi Celestino Córdova and demanding justice for the Mapuche people.

The thriving Mapchue community engages in various forms of activism as they fight for recognition and equity in Chilean society, one of which is through art murals. Below is a mural depicting the Machi wearing the trapelacucha and the equatorial cross symbolizing the essential life balance of the Mapuche people.

Recommended Reading

Shamans of the Foye Tree: Gender, Power, and Healing among the Chilean Mapuche by Ana Mariella Bacigalupo

Drawing on anthropologist Ana Mariella Bacigalupo's fifteen years of field research, Shamans of the Foye Tree: Gender, Power, and Healing among Chilean Mapuche is the first study to follow shamans' gender identities and performance in a variety of ritual, social, sexual, and political contexts.

To Mapuche shamans, or machi, the foye tree is of special importance, not only for its medicinal qualities but also because of its hermaphroditic flowers, which reflect the gender-shifting components of machi healing practices. Framed by the cultural constructions of gender and identity, Bacigalupo's fascinating findings span the ways in which the Chilean state stigmatizes the machi as witches and sexual deviants; how shamans use paradoxical discourses about gender to legitimatize themselves as healers and, at the same time, as modern men and women; the tree's political use as a symbol of resistance to national ideologies; and other components of these rich traditions.

The first comprehensive study on Mapuche shamans' gendered practices, Shamans of the Foye Tree offers new perspectives on this crucial intersection of spiritual, social, and political power.